The Sun isn’t working the way we thought it did. Many astrophysicists haven't actually understood one aspect of how the Sun worked––until former senior research associate Nick Featherstone and senior research associate Brad Hindman set the record straight.

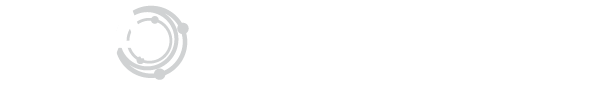

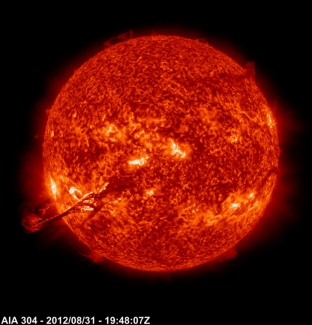

Stars like the Sun have to get rid of the heat generated by thermonuclear reactions in their centers. The Sun’s secret is vigorous convection, particularly in the outer third of the Sun closest to its surface. Like a pot of boiling water, hot fluid moves upward and cooler fluid moves downward, carrying heat outwards toward the surface of the star. For a long time, astrophysicists thought these motions came in two different sizes called granules (because these megameter-sized structures looked like grains of rice through early telescopes) and giant cells.

The trouble with the giant cell idea is that while granules appear on the Sun’s surface, giant cells have never been seen in spite of the fact astronomers have been looking for them for a long time. And, if giant cells exist, they would be 200 megameters1 wide, which is definitely large enough to be detectable. For instance, the largest cells seen in the Sun, called supergranules, are only about 30 megameters wide. Featherstone’s and Hindman’s new theory explains why supergranulation appears and why giant cells are absent.

The Physics Frontiers Centers (PFC) program supports university-based centers and institutes where the collective efforts of a larger group of individuals can enable transformational advances in the most promising research areas. The program is designed to foster major breakthroughs at the intellectual frontiers of physics by providing needed resources such as combinations of talents, skills, disciplines, and/or specialized infrastructure, not usually available to individual investigators or small groups, in an environment in which the collective efforts of the larger group can be shown to be seminal to promoting significant progress in the science and the education of students. PFCs also include creative, substantive activities aimed at enhancing education, broadening participation of traditionally underrepresented groups, and outreach to the scientific community and general public.

The Physics Frontiers Centers (PFC) program supports university-based centers and institutes where the collective efforts of a larger group of individuals can enable transformational advances in the most promising research areas. The program is designed to foster major breakthroughs at the intellectual frontiers of physics by providing needed resources such as combinations of talents, skills, disciplines, and/or specialized infrastructure, not usually available to individual investigators or small groups, in an environment in which the collective efforts of the larger group can be shown to be seminal to promoting significant progress in the science and the education of students. PFCs also include creative, substantive activities aimed at enhancing education, broadening participation of traditionally underrepresented groups, and outreach to the scientific community and general public.